According to an INSEE study, 3% of employees in 2017 declared that they practiced teleworking at least one day a week. Last June, this concerned 24% of employees. While confinements have enabled the rapid adoption of new digital tools and processes that make remote working more fluid, managers and employees are for the most part poorly trained by companies in these new practices.

So how do you deal with the corollary difficulties of working remotely? How to reduce "zoom fatigue", this exhaustion linked to the multiplication of videoconferencing sessions, when we also know that teleworking can also, in an apparently contradictory way, generate a feeling of loneliness?

Companies today face a major challenge: maintaining the engagement, productivity and collaboration of their employees working remotely. Could better online communication tools be an answer? A new generation of startups think so, provided they recreate a digital experience that is similar to that experienced by office workers when they come to work in their company's workspaces. Inspired by the world of gaming, these startups, like Gather, offer to join an online virtual office where the employee, thanks to his avatar, can walk around as he pleases in this metaverse supposed to facilitate replication. modes of interaction operating in a physical office. The enthusiasm for this type of tool is such that the global virtual office market is expected to grow by 21.9% in one year and go from 27 billion dollars in 2020 to 32.9 in 2021.

The digitization of work has made it possible to dissociate work from where it is done

The appearance of these virtual HQs or virtual offices (in other words “virtual offices”) is part of a larger trend: the gamification of work tools. This phenomenon has been made possible by the progressive digitization of work since the end of the 1990s. It is interesting to note that " virtual office " designated in the early 2000s a new way of working involving the use of the telephone, the email and Internet rather than face-to-face collaboration. It is on the basis of this boom in new information and communication technologies (NTIC) that it is then conceived to dissociate the “office” as a physical place from where the work is done. Work, because it can now be done online and therefore everywhere, then becomes “virtual” and mobile.

The question of the organization of online information then arose: how to allow employees to easily access the data necessary for their tasks if they are not on company premises? The answer was the creation, during the 2000s, of intranets, i.e. online portals from which employees could access, for example, company news or the employee directory.

The widespread adoption by the general public of social networks such as Facebook (created in 2004) and Twitter (created in 2006) subsequently led to a revival of these intranets, which then incorporated a social component. Facilitating communication and collaboration between teams and employees, the gradual integration of new digital tools such as instant messaging, HR tools, etc. transforms these formerly very static intranets into true hubs: this is the advent of the digital workplace .

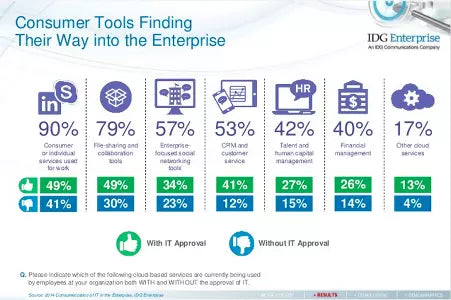

The consumerization of work tools has paved the way for their gamification

The digitization of work tools has also been accompanied by their progressive consumerization. In 2005 , Gartner declared that consumerization was "the most important trend affecting IT for the next ten years". This phenomenon results in the diffusion of a technology initially developed for the B2C market in the B2B sphere. It was made possible because the border between the private sphere and the professional sphere has been refined over the last decades due to the very digitization of work, the smartphone being at the heart of this process. So it's no coincidence that Facebook launched its enterprise social networking tool Facebook at Work in 2016.

The shift from the consumerization of work tools to their gamification has taken place in recent years thanks to the growing success of video games with the general public. “Gamification”, a term that first appeared in 2008, was defined in 2011 by researchers Sebastian Deterding, Dan Dixon, Rilla Khaled and Lennart E. Nacke as “the use of game design elements in contexts not related to video games”. With the development of new technologies such as 4G or the cloud, and smartphones and computers now capable of supporting applications that consume storage space and data, the soil was favorable to the distribution of video games that were once reserved for a market of passionate. Today, thanks to the smartphone, they reach all strata of society: in 2020, mobile games accounted for nearly 50% of video game revenues worldwide, thus familiarizing millions of users with codes and video game interfaces.

Des plateformes comme Centrical, adoptées par des entreprises comme Microsoft, démontrent l’efficacité de ces outils, avec une hausse de la productivité de 10 % et une baisse de l’absentéisme de 12 %.

Gamification continues in the B2B market with the explicit application of gaming codes to work tools. For example, startup Centrical recently raised $32 million for its platform that tracks employee engagement, development, and performance through gamified experiences. It has already won over major groups such as Novartis, Verizon and Microsoft, according to which the adoption of the tool has made it possible to increase the productivity of its center agents by 10% and to reduce the rate of short-term absenteeism by 12%.

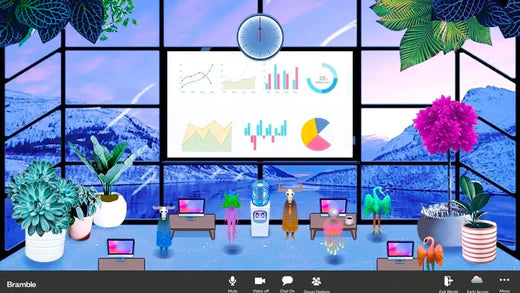

A study by Achievers Workforce Institute finds that since the pandemic, 46% of respondents feel less connected to their company, while 42% say company culture has faltered since the start of the pandemic. Only 21% consider themselves to be very engaged at work. Could the gamification of corporate communication tools overcome these three pitfalls? Since the start of the pandemic, more than a dozen startups have appeared that have recreated a spatialized universe online where users can walk around and interact with the environment or other users. Here (2020), Gather (2020), Nooks (2021), Branch (2020), Teamflow (2020), OpenTeam (2020), Teemyco (2019) and Bramble (2020), to name only the best known, all offer an innovative new communication tool for companies with employees working remotely.

Virtual offices offer a more playful and immersive experience than traditional communication tools

The virtual replication of physical workspaces could be a solution to promote the processes of socialization and serendipity at work in workspaces. The rapid arrival of these new tools responds in any case to an urgent need to find new working and collaboration methods adapted to remote work, which has become almost widespread. Directly inspired by successful video games such as The Sims , World of Warcraft or Empire , some of these startups are positioning themselves both as the new corporate intranets and as an alternative to Zoom and Slack deemed too limiting. The objective is clear: it is a question of putting the user-friendliness of the experience of face-to-face work at the heart of remote work thanks to a playful and immersive experience.

On the design side, the biases differ according to the companies however. Gather, for example, proposes to recreate the workspaces in 2D in a style reminiscent of the Zelda and Pokémon games. Using the arrows on his keyboard, the user can walk through the digitally replicated workspaces. He can thus find collaborators in special areas such as a meeting room where he can automatically join the other collaborators who are there by videoconference, or wander in certain zones such as the cafeteria where he can meet other colleagues for informal conversations.

Gather's design can feel archaic in many ways, especially when compared to other tools like Nooks. This other startup launched its platform in May 2020 to offer a virtual office designed for companies with teams based in different offices. Unlike Gather, Nooks does not offer a 2D replication of office spaces but chat spaces that employees can join at any time for brainstorming sessions, meetings or informal breaks. Once the user has clicked on the chat group he wants, he joins the virtual room composed of an image in the background like a meeting room or a kitchen table. From there, he can discuss and collaborate effectively, in particular thanks to the integration of more than 200 work tools such as Google Docs, Figma, or Notion. However, the principle remains the same: it is up to the employee to walk around and meet his collaborators by clicking on the different chat groups.

Virtual offices can promote proximity bias

The risks inherent in virtual HQs are similar to those of open-space or even greater. In addition to the risks of loss of productivity linked to too playful use of the tool, stress linked to expected over-communication, or even an imbalance between professional and private life, these tools could reinforce the bias of proximity already at work in workspaces.

Physical proximity is indeed a key factor in collaboration, which could play against employees working remotely. Dr. Sara Beth Kiesler, a professor at the Institute of Human-Computer Interaction at Carnegie Mellon University, explains in her article What Do We Know about Proximity and Distance in Work Groups? A Legacy of Research published in 2002 that the physical distance between offices and between workplaces directly and strongly impacts informal and spontaneous communication opportunities (passing each other in the cafeteria, at the end of a meeting, etc.). “These informal encounters increase the convenience and pleasure of communication, and they allow for unplanned and versatile interactions (...). Work in progress progresses more smoothly when people communicate often and spontaneously. Through spontaneous and informal communication, people can informally learn how each other's work is going, anticipate each other's strengths and weaknesses, monitor group progress, coordinate their actions, help each other each other and come to the rescue at the last minute when things go wrong”. As a result, “This implies that strong bonds will be more difficult to forge and maintain in the distributed workgroup than in the collocated workgroup”.

According to the researcher, the use of communication technologies is likely to be more effective when working groups have already established close relationships. As many companies move towards a hybrid operation with part of the employees on the premises and part working remotely, the harmful effects of the proximity bias are likely to be accentuated. This bias is defined as the unconscious tendency to favor people who are physically close to us because we know them better, because we can see them. It potentially involves a halo effect that would push employees and managers to overestimate those around them and to neglect more qualified but more distant people.

In his study Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment published in 2015, researcher Dr. Nicholas A. Bloom, professor of economics at Stanford, studying a Chinese travel agency, showed that employees working remotely had a higher performance but did not receive the same promotion opportunities, based on performance, as their employees working in the offices. In the long term, this bias can lead to numerous negative effects. Remote employees are more likely to lose trust in their team and manager. This can also negatively impact their productivity since they do not see their investment adequately recognized. Finally, in the long term, this can reinforce inequalities between employees, and a fortiori if some are already the subject of discrimination.

How to counter this proximity bias then? Some companies like Zillow and Salesforce, which have decided to adopt a flex office system, have for example changed the rules for holding their meetings: from the moment a member of a team works remotely, the employees present in the workspaces must each log on to their computer instead of gathering in a meeting room. Indeed, the company is considering installing screens in the kitchens of its offices to allow employees working remotely to engage in informal conversations with their collaborators. Within the Slack company, executives have agreed to work no more than three days in the office each week in order to lead by example. Others like Quora have decided to have all their teams work remotely in order to avoid potential biases related to hybrid operation.

Also, although these virtual office tools offer new perspectives on the socialization and collaboration processes of an organization and a breath of fresh air, it remains to be seen in the long term whether or not they really make it possible to preserve commitment. employees working remotely while avoiding the growth of inequalities and discrimination.

L’adoption du travail à distance implique d’adapter les méthodes de management

Les bureaux virtuels offrent une solution innovante pour la collaboration et la socialisation à distance, mais ils ne sont pas exempts de défis. Dans son étude Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment menée en 2015 sur une agence de voyage chinoise, le Dr. Nicholas A. Bloom a révélé que, bien que les employés travaillant à distance soient plus performants, ils accédaient moins souvent à des promotions que leurs collègues en présentiel. Ce déséquilibre peut générer une perte de confiance, une baisse de productivité et accentuer les inégalités, en particulier pour les collaborateurs déjà exposés à des discriminations.

Pour contrer ces biais, certaines entreprises adoptent des pratiques innovantes. Zillow et Salesforce ont instauré des règles obligeant tous les participants à se connecter individuellement en visioconférence lorsque des membres de l’équipe travaillent à distance. Slack limite la présence de ses cadres au bureau à trois jours par semaine pour promouvoir l'équité. Quora, de son côté, a opté pour un modèle entièrement distant afin de réduire les disparités liées au travail hybride.

Malgré leurs atouts, les bureaux virtuels soulèvent des questions à long terme quant à leur capacité à maintenir l’engagement des équipes tout en prévenant l’accroissement des inégalités. Selon le Dr. Bloom, les employés à distance risquent de ne pas voir leur contribution pleinement reconnue, renforçant ainsi un biais structurel déjà présent.